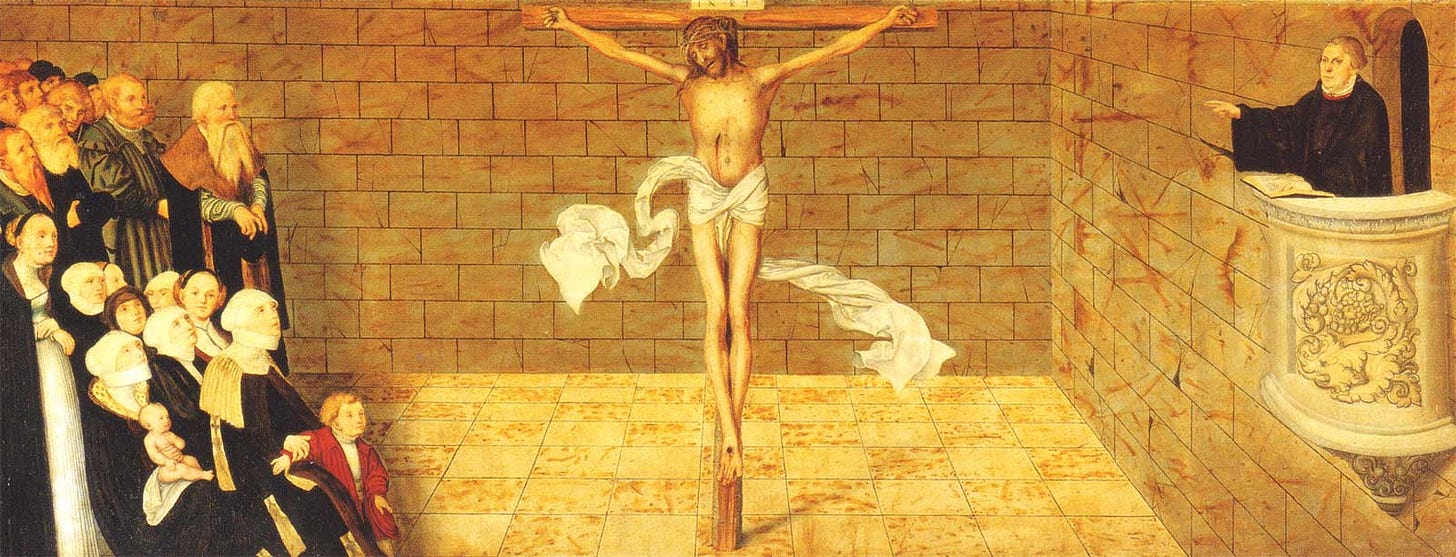

Here is a Holy Thursday sermon by our friend Dr. Ken Sundet Jones:

Maundy Thursday

Luther Memorial Church

Des Moines, Iowa March 28, 2024

After the Diet of Worms where he gave his “Here I stand” speech defying the Holy Roman Emperor, the various arrayed princes and representatives of imperial free cities, the representatives of the pope in Rome, and the prosecutor who demanded that he recant, this congregation’s namesake, Martin Luther, was wanted dead or alive. His prince Frederick the Wise executed a plan in which Luther was kidnapped by brigands but was really spirited away to the prince’s castle outside Erfurt, the Wartburg, on a hill almost in the clouds that he nicknamed the kingdom of the birds.

While he was there, Luther, who, as the most controversial person in Germany, had been subject to almost constant pressure from the demands and queries of others, not to mention the many tasks of life as a university professor and the daily schedule of worship, prayer, and study that was the life of a monk. Now in his lonely room all that was gone, his days were empty, and Luther, who’d grown out his shaved monk’s head and grown out his beard as a disguise and went by the alias of Knight George, found himself with time on his hands. It’s no surprise that Luther began writing letters to the people back home in Wittenberg whom he knew he could trust. In one of those letters, Luther responded to a question his fellow professor Philip Melanchthon had sent him. Philip, who was a layperson and one Germany’s most brilliant minds asked him for some advice: “How can I become a better preacher?”

You all may not wonder yourselves how you could become better preachers. In fact I suspect that, if you’re like most people, stepping into a pulpit to speak in public on behalf of God is something you’d take on like a root canal or back labor. But as we prepare to receive the Lord’s Supper, whose institution we remember this night, Phillip’s question is the flip side of ours. He asked how he could best deliver Christ’s gifts, and we must ask how we might best receive them.

Luther’s letter back to Melanchthon included a two-part answer. He told Philip that the first thing to do was to sin boldly. He should become not a sham sinner, but a real one, who recognized not just his mental list of commandments he’d broken, people he’d hurt or offended, and times when he’d placed himself first or judged others. Anyone can do that. No, sinning boldly meant doing something much harder, something that happens in AA meetings on a regular basis, something that the tax collectors, prostitutes, and law-breakers around Jesus had no problem doing. Luther told Phillip what he must do is know both his brokenness and its cause: his own skewed will. He must first know that none of the problem was anyone’s fault but his own.

No one likes to be the bad guy, especially when it means judgment and punishment because of your actions. I wonder if that’s not behind Jesus’ extreme actions in the time leading up to that Passover supper in the upper room. Three times earlier Jesus acted to force others to become out-and-out sinners, to make them carry out their actions against him.

On Sunday, as Pastor Kathleen so wisely reminded us, Jesus entered Jerusalem in a blatant thumbing of the nose to the power of the Roman Empire, its governor Pontius Pilate, and its occupying armies. Riding in on a donkey with crowds waving palm branches and crying out for him to save them was a stark contrast to Caesar who was regarded as a God and to Pilate who would have come through Jerusalem’s gates on a fine steed. Jesus’ actions were treasonous, and they set up Good Friday’s appearance before Pilate. Jesus basically forced the hand of the Roman authority figure who had the power to condemn him to death. In other words, he forced his judge to commit the sin of imposing the death penalty on him.

Then on Tuesday Jesus strode into the Temple where God’s people had to go to obtain the lambs they’d need for their Passover meals. The problem was that the coin of the realm that everyone was required for daily commerce had Caesar’s face on it. Those coins bearing a graven image of an idol weren’t allowed in the Temple, so the merchants provided a foreign exchange service where people could trade Roman coins for Temple coins, buy their lambs, and go home happy. But by tossing out the currency exchange staff, Jesus effectively shut down people’s ability to do their Passover law-abiding duty. He put an end to any false piety, but worse he cut into the priestly Passover profits. These are the same priests he would face after his arrest, the ones who’d argue for crucifixion before Pilate. So Jesus also forced their hands, pushed them into the blatant sin of seeking to end the life of the Son of God.

Finally, at the Passover meal itself, he pushedc Judas to go through with the dirty deed of betrayal. Jesus, who’d graciously included Judas in the meal with the other disciples, told him to go get it done. Judas was like a marionette hanging from Jesus’ hands. Within a day's span, Judas would hang elsewhere, but Jesus prodded him become a sinner, made him become the agent of betrayal whose very name would become slang for a two-faced faithless friend.

If Phillip Melanchthon or you have any hesitation about being a sinner, take heart. Jesus not only thinks sinners are the best company, he actually uses Pilate’s, the priests’, and Judas’ sin to accomplish what he’s come to Jerusalem to do: give himself up for your sake. As soon as you try to not be a sinner, you eliminate every task and responsibility on the Lord’s job description, and you leave Jesus with nothing to do but be a good example or arbiter of the law, neither of which he’s much interested in. Saving real sinners who can’t get their act together, who can’t even admit to wanting to improve themselves, who have no hope apart from him, now that’s material he can use to create the Kingdom of God.

Martin Luther telling Melanchthon to first be a sinner is equally good advice for anyone coming to Christ’s table of mercy. For that’s where you again hear the good news proclaimed: Jesus died at the hands of sinners and, more important, for sinners. Jesus’ body is torn and his blood spilled, so he can be what he urgently desires to be: your Lord.

Which brings us to the second part of Luther’s advice to that would-be preacher, Phillip Melanchthon. Luther told him to sin boldly but to trust all the more boldly in Christ’s mercy. For us coming to the Lord’s Supper tonight, Jesus makes the same pitch: trust me. That’s why he pushed Pilate, the religious leaders, and Judas to take such extreme actions: so you could see how fully and deeply the Lord is willing to commit to you and, in turn, trust him. He doesn’t come for religious superheroes or even for regular folks who think they might do better with a little effort. He comes for sinners, for Zaccheus the tax collector, for the woman caught in adultery, for scofflaws and cheats, and for you. He poured himself out on the cross not for people in general, but for you right in the depth of your selfishness, greed, pride, and reluctance to serve your neighbors.

When Luther wrote an explanation of the sacrament several years later in the Small Catechism, he said the most important thing in it isn’t the eating and drinking, instead, it’s the promise proclaimed. Jesus’ body anblood are given and shed for you. That means that when you come forward this evening and receive the bread and wine, it means coming as a naked sinner and returning as one from whom divine judgment has been lifted. So come you powerful, you pious, you betrayers, you craven sinners.

Maybe you still don’t believe me. Maybe you’re sitting where Peter is, and you’re still indulging the notion that you are the exception. Or maybe you don’t need me to convince you. Maybe you’re sitting where Judas is, and you’re nursing a betrayal. Or maybe you’re somewhere in between. Maybe you’re confused and you don’t know what to think. It doesn’t matter. Christ knows. And at this table, he offers himself to you all the same. And then his offering, it all comes to pass.

Nothing delights your Lord more than declaring to you that you, even if you were the chief among sinners, especially if you are the chief among sinners, you are forgiven. You are his.